EOM Chapter 14 How Exchange Systems Succeed or Fail

The End of Money and the Future of Civilization

Read this newest chapter from Thomas H. Greco’s revised and expanded The End of Money and the Future of Civilization.

(Audio narration can be found in the Future Brightly podcasts.)

The End of Money and the Future of Civilization

New 2024 Edition

Chapter Fourteen

How Exchange Systems Succeed or Fail

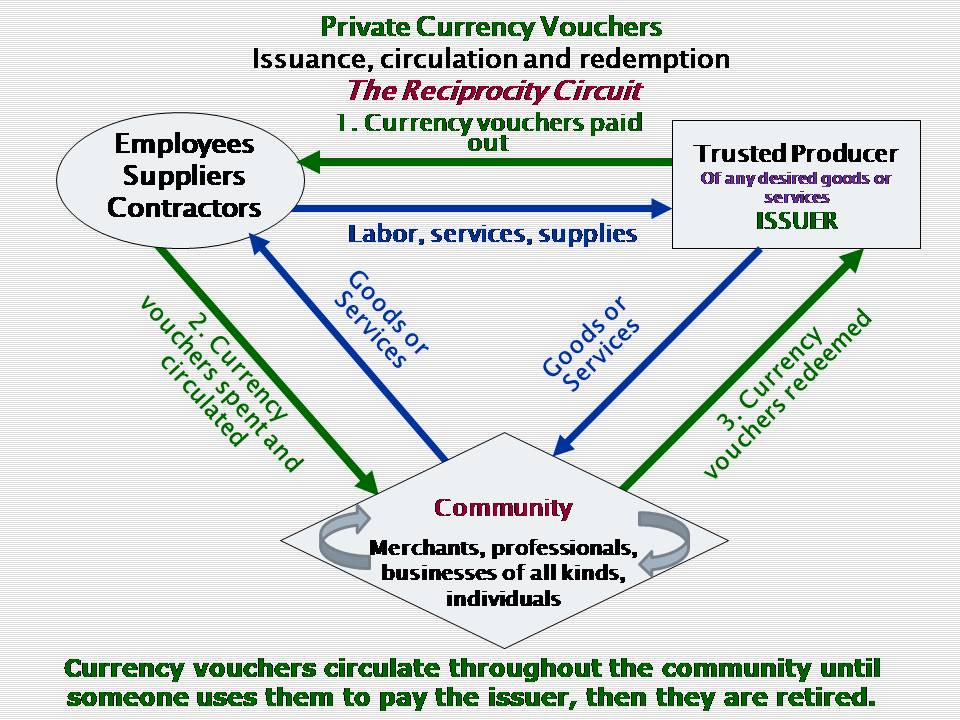

In our consideration of exchange alternatives, we have been discussing both complementary currencies and credit clearing as viable alternatives and complements to conventional money. The credits that exist within a credit clearing system can be thought of as a complementary currency, even though they may exist only as numbers on a ledger of accounts and circulate only within the credit clearing circle. Similarly, a currency is simply a manifestation of credits that originate from some issuer who spends them into circulation. Thus, we will use the terms currency and credits interchangeably, since they have the same essence. For the reader’s convenience we repeat here in Figure 14.1, the depiction of the reciprocal exchange process that was introduced in Chapter 8. It shows the complete circuit of issuance, circulation, and redemption/extinction of currency or credits. Reciprocity occurs only upon completion of the circuit. This should be kept in mind as we describe the various principles that relate to reciprocal exchange. Note that currency flows in one direction (the outer ring) while goods and services flow in the opposite direction (the inner ring), and that the original issuer eventually redeems the currency they issued by accepting it back as payment for the goods or services they have to sell.

Figure 14.1 The Currency Issuance, Circulation, and Redemption Circuit

Lessons Learned from 40 years of Research and Experimentation

Over the past several decades, many local and community currencies have come and (most of them) gone. By observing those outcomes, and by my own research and experience with Tucson Traders and LETS Sonora, several fundamental principles have become clear and have led to the prescriptions I have been offering. Here is a partial list:

1. A community currency, to be truly effective, must be more than a local version of existing political fiat money; it should not be sold for money but spent into circulation.

2. A community currency must be created independently of the banking system as it currently exists.

3. A community currency ought to be created by local producers and sellers of real value in the form of vouchers that they spend into circulation and are voluntarily accepted by other producers.

4. The amount of vouchers spent into circulation must not exceed the amount that an issuer is able to redeem by delivering goods and services within a few months’ time.

5. Such voucher currencies may wander away from the local community, but they must eventually return to the community to be redeemed by the issuer(s).

6. Voucher currencies must have an expiration date or demurrage fee to stimulate a healthy velocity of circulation, and to guarantee their timely redemption.

7. There needs to be a clear agreement between the issuers and users of a currency and adequate means of enforcing the provisions of that agreement.

The level of success of an exchange system is determined by a number of factors, which fall into these four broad categories:

1. The architecture of the exchange system or currency itself,

2. The management of the exchange system or currency,

3. The implementation strategies, and

4. The context into which the currency or exchange system is introduced.

Architecture of the Currency

The first requirement of any currency or exchange system is that it accomplishes its intended purpose, which is to effectively and efficiently facilitate the reciprocal exchange of value. We made the point in Chapter 9 that there are three modes by which economic value changes hands—as gifts, as involuntary transfers, or as reciprocal exchange. It is worth repeating that it is within the realm of reciprocal exchange that money or currency plays its fundamental role as an exchange medium or means of payment—that is its essential and only function. Grassroots organizers are often tempted to encumber their fledgling exchange systems with additional “baggage” that seeks to remedy all sorts of perceived problems and inequities, but well-intended as they may be, a currency is simply not able to perform these additional functions which actually require different tools and approaches. One common example of such “baggage” is the desire to use a community currency to provide a Universal Basic Income (UBI). However, a currency by itself cannot solve the problem of income maldistribution which UBI seeks to remedy, but it can address the exchange problem which once solved can set the stage for solving myriad other economic, social, and political problems.

A currency or credit system must be designed in such a way as to assure reciprocity in free-market exchange. As we described in Chapter Seven, The Nature, Cause, and Consequences of Inflation, it is necessary to consider both the quality of the currency or credits, and their quantity. There are a few critical design questions, the answers to which are all important in determining the success of a currency, i.e., its ability to hold its value and its ability to circulate widely and rapidly.

1. Who is qualified to issue currency?

2. On what basis should currency be issued?

3. How much currency may be spent into circulation by each issuer?

4. How long should a currency remain valid?

We will discuss each of these in turn, and we will consider the terms “money” and “currency” to be synonymous.

Principle 1: Who Is Qualified to Issue Currency?

A person, a business entity, or a governmental body is qualified to issue a currency if they are ready, willing, and able, to redeem their currency for goods or services that they have available to sell now or in the immediate future. A corollary to this principle is that such goods and services should be in everyday demand and be offered at prices that are published and competitive. E. C. Riegel has this elegant manner of expressing it:

“A would-be money issuer must, in exchange for the goods or services he buys from the market, place goods or services on the market. In this simple rule of equity lies the essence of money.”[1]

He further clarifies the point by saying, “He who would create money to buy goods or services must be prepared to produce goods or services with which to buy money.”[2]

The point is that money is a device we create for the purpose of facilitating reciprocal exchange. That means enabling a provider of valuable goods and services to receive equivalent value from someone else at some later time; it is a way of enabling traders to indirectly use the things we produce and sell to pay for the things we buy. Money or currency is a placeholder, an instrument that enables one who has delivered goods or services to requisition from the marketplace later on and from someone else, other goods or services that they might need or desire.

Principle 2: On What Basis Should Currency Be Issued?

Although it is largely ignored in today’s banking practice, it is a well-established sound banking principle that money should be issued on the basis of goods already in the market or on their way to market and soon to arrive. In its modern manifestation, money is nothing more than credit—but not all credit is suited to serve the exchange function. As depicted in Table 14.1, a distinction must be made between short-term exchange credit or turnover credit, and long-term finance credit or investment credit. Turnover credit can be thought of as representing the value of goods and services that are currently available for sale. It is the circulation of turnover credit among potential buyers which provides the means by which those goods can be bought and paid for. The issuance of currency as turnover credit provides the various actors in the economy with the purchasing power needed to buy those goods that they have collectively produced, which then removes them from the market.

Investment credit, on the other hand, is required to finance the capacity to produce goods and services that will only become available at a much later time, thus, investment credit must be long-term and come from savings; to do otherwise distorts market prices. Issuance of currency on the basis of long-term debt, such as mortgages on real estate, does not compel its timely reflux and redemption by the issuer. Take for example a farmer who decides to plant an orchard. He needs investment credit to acquire land, equipment, and tools, to buy the sapling trees, and to cover his living expenses for a few years until his trees mature and start bearing fruit. The people who provide him with those things deserve to get credit that represents a share of the future produce. How might their investment be recognized? The proper answer is that it should be recognized by giving them a financial instrument (call it a bond) that is redeemable (spendable) only when (and if) the crop is harvested. It would not be appropriate to give them recognition in the form of money/currency because currency is spendable now, but the crop will not arrive until later. It would not be appropriate for investors to be paid by issuing a currency because the farmer/issuer has no immediate means of redeeming it, i.e., reflux cannot begin until his first harvest. Timing is the salient factor in distinguishing turnover credit from investment credit.

Naturally, there must be some way for turnover credit to be effectively converted into investment credit and vice versa, and in fact such mechanisms are long established and well developed. The realm of finance provides various methods for both saving and investment. At any point in time, there are some who have an amount of turnover credits (the spendable kind of credit) that is in excess of their current needs. They wish to “save,” but at the same time, there are others who need additional turnover credits to, perhaps, start or expand a business that will later on put goods and services into the market. As in the above example, they might spend these turnover credits to acquire the means of producing marketable goods and services. This is the process known as capital formation. So, saving and investment are two sides of the same coin. One person saves by reallocating their temporary surplus of turnover credits to someone who wants to use them in a way that will lead to the production of goods and services later on. In this way, turnover credits are transformed into investment credits. The reverse process takes place when the investment is repaid out of income earned at the time that the new products and services go to market. In a currency system, as the product goes to market, currency can be created to redeem the bonds. Consumer credit used to finance consumer durables works in much the same way.

To sum up, an exchange medium (money/currency) should properly be, in essence, turnover credit, created on the basis of the near-term delivery of goods and services to the market. The financing of long-term assets or consumer purchases should not be the basis for money creation, but rather should be financed through the reallocation of money that already exists and is being “saved.” In the political money system, this rule is commonly violated. It is one form of currency inflation that leads to an increasing general price level. In the absence of legal tender status, an inflated currency will begin to pass at a discount relative to an objective value standard. In sum, the application of this principle requires the following rules regarding the issuing of money (turnover credit):

· Disallow the creation of money on the basis of government debt, which puts no additional product into the market.

· Disallow the creation of money to finance consumer purchases, which take goods from the market.

· Disallow the creation of money to finance capital expansion (long-term assets), which does not immediately put goods and services into the market.

The relevant argument, then, is not between credit money on the one hand and commodity money on the other, but between credit money that is properly issued and credit money that is improperly issued.

Principle 3: How Much Currency May Be Issued?

A critical factor in the circulation of any currency is what bankers traditionally refer to as the velocity of circulation or “reflux rate,” which is the rate at which a currency returns to the issuer for redemption, at which point, having fulfilled its purpose, it then ceases to exist. In the absence of legal tender laws, a currency with too slow a reflux rate will be devalued by traders in the market. It will either be refused outright as payment, or accepted at less than face value or “discounted,” as shown in Figure 14.2. That is why a currency should be issued on the basis of goods and services that have a high everyday demand. Such a basis will guarantee that the circulation of the currency will be rapid and frequent, and not accumulate in the hands of those who have little opportunity to spend it.

Figure 14.2 Currency Discounts from Face Value

Here we need to consider the time factor. How long does it take from the beginning of the production process to the end when the product goes to market? Each line of business has its own peculiar production and distribution pattern that determines its annual turnover rate, but we know from experience that the average overall turnover is about four times a year. That means that about one quarter of annual production is in the market and ready for sale at any given time. Enough currency or “turnover credit” should be provided to enable that amount of goods and services to be purchased. Based upon the reflux guidelines discussed above, it is reasonable that the issuance limits on each account be based on this practical rule of thumb: each issuer may issue an amount of currency that is no more than their historical average of sales over a period of about one hundred days (roughly three months), which implies a daily reflux rate of 1%. For example, if a local co-op grocery is a member of a mutual credit clearing association, and it has annual sales of 1 million dollars, its maximum debit balance could be limited to 250,000 dollar-credits.

The actual starting point for a complementary currency or clearing exchange should be well below that limit, building up gradually over time as sales capacity into the community or clearing circle is demonstrated, but it should never be allowed to exceed the three months average sales limit. Even this upper limit, however, might need to be adjusted upward or downward in response to the actual performance of the currency in the marketplace. The critical indicator is the value rate at which the currency actually passes in the marketplace. If it is being accepted only at a discount from face value, that is an indication that it has been overissued or improperly issued, in which case the rate of issuance should be slowed to match the rate of redemption. Remember that we use the word “redemption” to mean the issuer’s acceptance of the currency as payment for his goods and services, not redemption in official currency, nor any other “currency reserve” like gold or silver.

“Pooling” and stagnation are problems that have afflicted many community currencies. Local currency organizers often complain that their most difficult task is getting people and businesses to accept the currency. My advice is always the same: don’t try to push your currency on anyone; allow it to be pulled along through the economy by the natural demand for it. Like a string, a currency does not respond well to pushing—but it does respond to pulling, and a properly issued currency will be naturally propelled through the economy. What is this natural force that propels a currency? It is the promise and obligation of an issuer who is ready, willing, and able to redeem their currency by accepting it in payment for the goods and services they have to sell.

The bottom line is this: most of the issuing power (lines of credit) should be allocated to those businesses in the community that are able to offer the greatest amount of valuable goods and/or services; these are the businesses that people readily trust and are eager to buy from. There would be no difficulty, for example, in getting a currency to circulate if it were issued, say, by the local gas company, or electric utility, or water company, or large retailer telephone company, or . . . well, you get the idea. Likewise, a currency issued by a major retailer, or repair shop, would also be valued and accepted. If a company is not already overburdened with debt obligations, and its issuance is not excessive, almost everyone in the community will accept that company’s voucher currency without hesitation because almost everyone has a gas bill or electric bill or water bill or telephone bill to pay. Even those who do not do business with the issuing company will accept it because of the large number of others in the community who do. So long as such a company agrees to fulfill its obligation by accepting its currency at face value in payment for its services, it will have no difficulty in getting its suppliers, contractors, and employees in the community to accept it as payment, and they in turn will have no difficulty in finding merchants in the community willing to accept it in payment. From then onward, the currency can pass throughout the community, from one user to another until it is redeemed or expires.

Principle 4: How to Determine the Period of validity?

A basic need in creating a healthy community economy is to have its own source of liquidity, i.e., a sound supplemental means of payment that is independent of the banking system. A currency has a limited lifespan; it is created when an issuer spends it into circulation, and extinguished when the reciprocity circuit is completed by the issuer accepting it back as payment. But in the meantime, a community currency is meant to circulate widely to enable settlement of other peoples’ obligations. While Principle 3 requires a sufficiently rapid reflux to ensure that the currency will continue to be accepted at face value, we would like the reflux rate to be slow enough for the currency to be useful as a general payment medium, meaning that it will change hands numerous times and clear obligations among others before it is redeemed by the issuer. So, when considering the life span of a currency, there is an optimum or sweet spot. I refer to this as the “Goldilocks point”—the life span, which is neither too long, nor too short, but just right to fulfill its mission. Experience shows a maximum lifespan should be somewhere around 100 days, but what would be a desirable minimum for the currency to serve the community as an independent payment medium? Since the reflux rate is directly related to the quantity of currency that is issued into circulation, the lifespan of the currency will increase as more is issued and decrease as the currency supply in circulation decreases through redemption. Thus, by regulating the rate of issuance and the rate of redemption, a currency will find its sweet spot.

If a currency is in the form of a paper note or voucher there is the possibility of it being kept out of circulation or hoarded. That can, and should, be prevented by specifying an expiration date or demurrage fee (which is sometimes referred to as “negative interest”) by which the nominal value of a currency note, or credit balance, is gradually reduced. Hoarding of ledger account balances can be prevented if there is an agreement that surplus credits above a certain amount in an account will be automatically loaned out or otherwise invested.

Implementation Strategies

For alternative exchange media, as for any other innovative product, if one wishes to make inroads into markets where there are entrenched products or patterns of behavior, one must employ means that are capable of making an impression upon the public mind and shifting people’s purchasing decisions or lifestyle choices. Having a superior product is not enough. People must be made aware that the superior product or service exists, they must be persuaded that the advantages of adopting it outweigh the risks and disadvantages, and the product must be made easily available at a price they can afford. There are insights to be gained from the study of natural and social phenomena. In the natural realm, the growth of animal and insect populations and the spread of infectious diseases reveal certain laws that also seem to apply to the market and the spread of ideas. Fashions and fads are phenomena of massive and sudden behavioral change. How do they get started? What gives them their impetus? How and why do they die out?

Malcolm Gladwell, in his book The Tipping Point, highlights three basic elements that can trigger such radical change. He calls them The Law of the Few, The Stickiness Factor, and The Power of Context.[3] The stickiness factor has to do with the nature of the thing being propagated—in our case, the architecture or characteristics of the currency option (which we’ve already covered above). “The power of the few” means that a few people making small changes can cause a big effect that happens quickly. Gladwell argues that “ideas and products and messages and behaviors spread like viruses do,”[4] and he draws insights on these things from what is known about disease epidemics.

So, if we wish to foster changes of a cultural, social, economic, or political nature, what lessons from nature can we educe and apply? The salient few, in Gladwell’s view, are comprised of three types—the mavens, the connectors, and the salesmen. Mavens “provide the message”; they are teachers or “information brokers.” They are the ones who “know everything” about a particular subject—and they not only possess information, but they also love to share it. Connectors spread it. They are sociable people who tend to “know everyone,” and can bridge the gaps between otherwise unrelated social groups. They provide the “weak ties” that help ideas to spread widely and quickly. Salesmen persuade people to adopt, use, or buy it. They have that mysterious knack for getting people to trust them, to agree with them, and to take a particular action.[5] The best salespeople, of course, are those who combine sales talent with belief in what they are selling. They are genuinely trying to be helpful and have a missionary zeal about getting others to use their product.

Gladwell’s work has provided a helpful overview, but deeper understanding can be gained by consulting others who have made a thorough study of what are called self-organizing systems or networks. Laszlo Barabasi, in his book Linked: The New Science of Networks, shows how networks in diverse and seemingly unrelated fields share similar properties.[6] A detailed elaboration of those points is beyond our scope here, but an example from his book will be helpful in elucidating the point—the impressive success of Hotmail.

At the time that Hotmail was introduced, the use of e-mail communications was already a popular and growing phenomenon, a wave that Hotmail managed to ride in a way that enabled it to capture a major portion of the e-mail accounts then in use. Barabasi asked,

“What is the source of Hotmail’s phenomenal success? . . . Hotmail enhanced its spreading rate by eliminating the adoption threshold [that] individuals experience. First, it is free; thus, you do not have to think about whether you are making a wise investment. Second, the Hotmail interface makes it very easy to sign up. In two minutes, you have an account; thus, there is no time investment. Third, once you sign up, every time you send an e-mail you offer free advertisement for Hotmail. [At the end of each e-mail message sent by a Hotmail user the recipient saw the Hotmail Web address and an offer to set up their own free Hotmail account.] Combine these three features, and you get a service that has a very high infection rate, a built-in mechanism to spread. Products and ideas spread by being adapted [adopted?] by hubs, the highly connected nodes of the consumer network.”[7]

Similar strategies have been employed by countless major players in Internet commerce, like Google, Yahoo!, and others. Google and Yahoo both offer free email accounts, while Amazon has captured the lion’s share of e-commerce by offering a wide range of products offered by myriad sellers, and providing free delivery on orders above a relatively low threshold amount.

The Situational Context

Sometimes major changes occur in response to a crisis situation, as was the case with the Swiss WIR and the scrip currencies that emerged during the Great Depression of the 1930s, and the more recent Argentine Trueque phenomena described in the previous chapter. Or it could be some other “black swan” event that changes the broader societal context, like the COVID-19 “pandemic” that began in 2020 and triggered some unprecedented and controversial political, social, and economic reactions. People were forced to “social distance,” avoid gathering in groups, and wear masks. A great many (mostly small) businesses that were deemed “non-essential” were forced to close, many of which, unable to sustain the losses, never reopened. As the experimental “vaccines” were rolled out, innumerable workers, despite the lack of proper testing and full disclosure, were mandated to accept the “jab” or lose their jobs—and their incomes. Central governments pulled out all the stops on spending, sending budget deficits into the stratosphere and enabling massive shifts in the distribution of wealth from the middle class to echelons of the extremely wealthy.

Another remarkable outcome was the massive increase in virtual meetings. The Zoom platform, for example, went from 10 million daily meeting participants at the end of 2019 to over 300 million by April 2020, and has continued to expand from there along with other virtual conferencing apps from Google and Microsoft and others. This has also resulted in a massive shift from working in offices to working from home. A great many companies have not only allowed employees to work from home but have forced them to do so by closing their offices. This has allowed companies to reduce their overhead costs and shift that burden onto their workers. That trend has resulted in large increases in vacancy rates of commercial properties, especially office spaces, while at the same time increasing the demand and cost of residential real estate, which has contributed to the further decline of the middle and lower classes.

How might these adverse trends be reversed? As I have argued throughout, the money power must be depoliticized and reasserted by the people who are the real producers of real value.

[1] E. C. Riegel, Flight From Inflation, p. 16 (p. 23 in digital file) at https://beyondmoney.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/flight.pdf.

[2] Ibid. p. 24 (p. 29 in digital file).

[3] Malcolm Gladwell, The Tipping Point, p. 19.

[4] Ibid. p. 7.

[5] Ibid. p.70.

[6] Laszlo Barabasi, Linked: The New Science of Networks.

[7] Ibid. pp. 214–15.